-

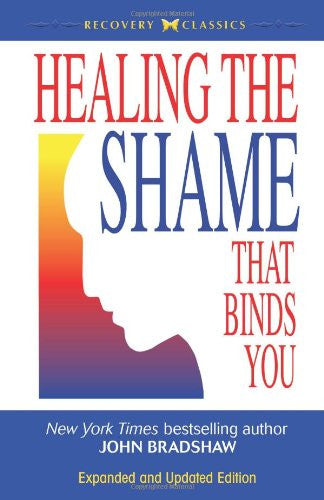

Healing the Shame that Binds You (Recovery Classics)

Miscellaneous

-

$13.28

-

is back-ordered. We will ship it separately in 10 to 15 days.

-

-

Description

John Bradshaw is a counselor, speaker and one of the leading voices of the recovery movement, especially inner child and family issues. His classic books include Healing the Shame that Binds You (1.3 million copies sold), Bradshaw on: The Family (1.2 million copies sold) and Homecoming (3 million copies sold). PART I The Problem— Spiritual Bankruptcy We have no imagination for Evil, but Evil has us in its grip. —C. G. Jung Introduction: Shame as Demonic (The Internalization Process) As I've delved deeper into the destructive power of toxic shame, I've come to see that it directly touches the age-old theological and metaphysical discussion generally referred to as the problem of evil. The problem of evil may be more accurately described as the mystery of evil. No one has ever explained the existence of evil in the world. Centuries ago in the Judeo-Christian West, evil was considered the domain of the Devil, or Satan, the fallen angel. Biblical scholars tell us that the idea of a purely evil being like the Devil or Satan was a late development in the Bible. In the book of Job, Satan was the heavenly district attorney whose job it was to test the faith of those who, like Job, were specially blessed. During the Persian conquest of the Israelites, the Satan of Job became fused with the Zoroastrian dualistic theology adopted by the Persians, where two opposing forces, one of good, Ahura Mazda, the Supreme Creator deity, was in a constant battle with Ahriman, the absolute god of evil. This polarized dualism was present in the theology of the Essenes and took hold in Christianity where God and his Son Jesus were in constant battle with the highest fallen angel, Satan, for human souls. This dualism persists today only in fundamentalist religions (Muslim terrorists, the Taliban, the extreme Christian Right and a major part of evangelical Christianity). The figure of Satan and the fires of hell have been demythologized by modern Christian biblical scholars, theologians and philosophers. The mystery of evil has not been dismissed by the demythologizing of the Devil. Rather, it has been intensified in the twentieth century by two world wars, Nazism, Stalinism, the genocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, and the heinous and ruthless extermination of Tibetans and Tibetan Buddhism by Pol Pot. These reigns of evil form what has been called a collective shadow, and it has been shown how naïve and unconscious the people of the world have been in relation to these evils. The denial of evil seems to be a learned behavior. The idea of evil is always subject to denial as a coping mechanism. Evil is real and is a permanent part of the human condition. 'To deny that evil is a permanent affliction of humankind,' says the philosopher Ernst Becker in his book Escape from Evil, 'is perhaps the most dangerous kind of thinking.' He goes on to suggest that in denying evil, humans have heaped evil on the world. Historically, great misfortunes have resulted from humans, blinded by the full reality of evil, thinking they were doing good but dispensing miseries far worse than the evil they thought to eradicate. The Crusades during the Middle Ages and the Vietnam War are examples that come to mind. While demons, Satan and hellfire have been demythologized by any critically thinking person, the awesome collective power of evil remains. Many theologiams and psychologists refer to evil as the demonic in human life. They call us to personal wholeness and self-awareness, especially in relation to our own toxic shame or shadow, which goes unconscious and in hiding because it is so painful to bear. These men warn against duality and polarization. 'We must beware of thinking of Good and Evil as absolute opposites,' writes Carl Jung. Good and evil are potentials in every human being; they are halves of a paradoxical whole. Each represents a judgment, and 'we canno